Witness, survivor, victim, activist, these proper nouns are attached forever to the 1980s AIDs epidemic, when an insidious, unknown virus struck, viciously.

Suddenly, improbably, death overwhelmed life, and everyone was so young. “I’m positive” or “he’s gone, he’s dead” became common conversation. In NYC, where I live, from 1980 through 1996 the unimaginable happened again and again. No one who had AIDs expected to live.

Memorializing is enacted by witnesses and survivors who struggle to account for the devastation of their communities — in words, paintings, films, photographs. Some survivors feel like living memorials. Forgetting is impossible, and wrong. To forget lovers, friends, brothers, sisters would be a second death for them.

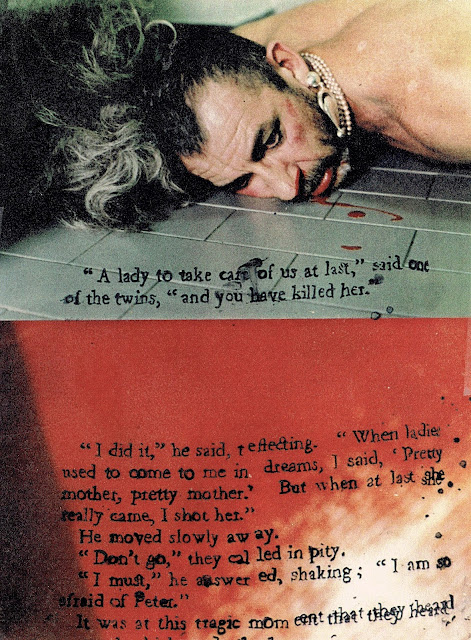

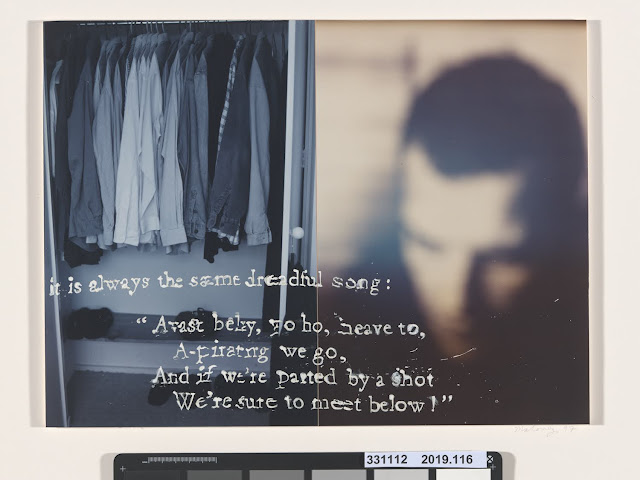

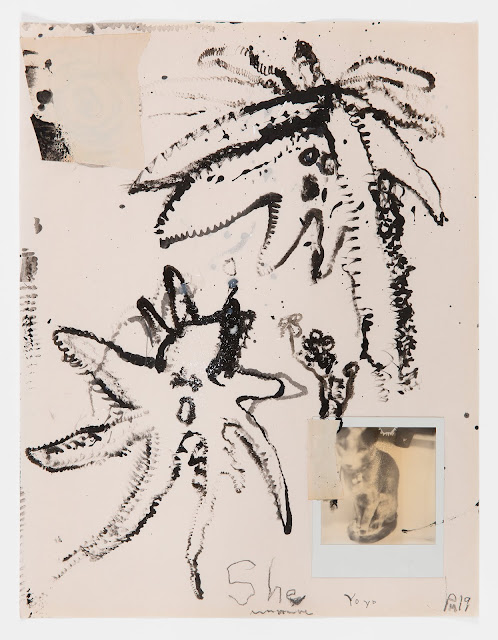

Peter Maloney’s photographs remember, imaginatively, uniquely. His images are fictional memorials, inventions of and from that past. The photographs come to synthesize feelings, to possess, I think, and express an extraordinary sensation — I want to call it “numbness.” A numbness from loss after loss, memorial service after memorial service. Deadened emotion permeated an overwhelmed gay community, and its friends. Exhaustion was common, experienced by those who were sick and those helping them.

In New York City, artist David Wojnarowicz declared: after he died, he wanted no memorial. They were so numerous and routine, it was painful, and to him useless. So, on the day he died, a ragtag group of people paraded down Second Avenue — by chance I was at the corner on Tenth Street and joined — to Astor Place. In a vacant lot, they burned anything they could find, it was a bonfire of futility. The small group stood there, helpless to do anything. The virus carried hopelessness.

Any of us who lived through and after that time find it almost impossible to explain to people who didn’t what it was like. Maloney’s photographs reckon with that problem, focusing on how time was experienced, the way certain poets gainsayed the anguish of war.

I knew a simple soldier boy

Who grinned at life in empty joy,

Slept soundly through the lonesome dark,

And whistled early with the lark.

In winter trenches, cowed and glum,

With crumps and lice and lack of rum,

He put a bullet through his brain.

No one spoke of him again.

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you'll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

----Siegfried Sassoon, 1918

Maloney’s images nearly fade before your eyes, the way faces do when you begin to forget and fight to keep them there. People appear to fade into the ages, yet their images stay as if already imprinted. Was it a nightmare, a fantasy, could this have really happened, his pictures say.

Survivors of that AIDs era, alive now because of protease inhibitors, don’t feel victorious. Like all who watch others die, they wonder why not me. Maloney’s art depicts their sadness also; the silencing of friends and lovers, and the humbling death inflicts.

Most alive now don’t know about that period, and though COVID will be compared with the AIDs pandemic, it was and is very different. And, AIDs is not over, there is no vaccine for it. Medicines exist to retard its progress, keep the viral load low, but the inequities of the world, poverty, stop the medicines at borders.

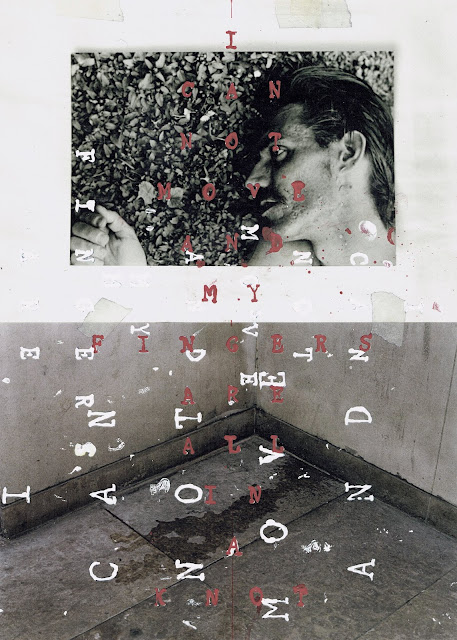

To describe Maloney’s photographs is difficult — they are composed, metaphorically, of absence. In YOU BECAME (a) TIME PAST 170397, a man’s face and the eponymous title collude. The face looks out, with illegible letters on it, the face is barely legible. Blurs, erasures, missing letters, all are analogues to future disappearance. To look at the man’s blurred face, to recall what AIDs wrought, one can imagine oneself in a distressed mirror.

The man’s present has already moved into the past. “You became a time past” in the other picture alludes, perhaps, to Proust’s time past, but no madeleine dissolves on the tongue, no pleasant sensation returns with memory. The sentence is printed on a brick wall. The space is grim, harsh, a corner makes the vanishing point, and there is no bottom, just an endless fall.

Illegibility and blur connote that time, and in Peter Maloney’s photographs their use represents the impossibility of capturing those years, those losses — the way people were stunned again and again by rapid death. The work speaks to the daily horrors people felt. Maloney’s impressive body of work moves me. The images are indelible, they stay with me, and remind me of so much I can never forget.

Lynne Tillman

June 2021